In 2020, the UK Met Office began working with British-American insurance broking company WTW formerly known as Willis Towers Watson to develop more accurate one to five-year hurricane forecasts and shape insurance products for coastal properties along the Atlantic coast of the US.

At the time, the UK Met office provided a forecast of North Atlantic hurricane activity and hurricane induced US insured losses for the period 2020-2024 based on predictions made in November 2019. They forecast a more than 95% chance of above average hurricane activity and a corresponding over 95% likelihood of above average hurricane induced US insured loss during this period.

So far, although the 2024 North Atlantic hurricane season which runs from 1 June to 30 November has yet to happen, the predictions have been accurate.

A paper published in the Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology explained that the potential forecast products developed could ‘provide some guidance for how insurers may think about hurricane risk in the next few years, and can become part of the underwriting conversation in selecting which lines of business to grow or shrink’.

Back in 2019, the initial project was to develop prototype forecasts for the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) website. C3S supports society by providing authoritative information about the past, present and future climate in Europe and the rest of the World.

North Atlantic hurricane activity and insurance

Historically, North Atlantic hurricane activity has varied substantially according to decadal timescales. On average there are 40% more hurricanes and more than twice as many major hurricanes in active periods relative to quiet periods.

The 1900s to the 1920s and 1970s to the 1980s were relatively quiet. The 1930s to the 1960s were active. Since 1995, we have been in an active period.

Hurricane damage also varies considerably from decade to decade. During the 1996-2005 decade, average annual hurricane damage in the continental United States was approximately $20 billion (normalized to 2005 values). This compares with less than $4 billion for the decade 1976-1985.

Inevitably, hurricane damage is expected to rise further if the increasing concentration of people and property in coastal regions continues. There is therefore a need for more skilful predictions of hurricane activity, along with improved understanding of the causes of variability, to inform potential adaptation and mitigation strategies as well as risk assessment.

For the property and casualty (PC) insurance industry which typically underwrites annual contracts and may have substantial automatic renewals, being able to accurately quantify hurricane risk on short to medium time scales, from the next season up to 10 years, would have major economic benefits.

Image supplied by the UK Met Office

Decadal predictions

Multi-year Atlantic hurricane forecasts of the kind pioneered by the Met Office benefit from the recent development of better initialised climate prediction also known as decadal forecasting.

As Dr Julia Lockwood, the Senior Scientist at the Met Office who oversaw checking the accuracy of the initial models and has been involved with the project from the beginning, explains, ‘In these initialized climate models, which we call decadal prediction systems, it’s important to start with the right observations and that’s where the global ocean observing network comes in..’

For example, ‘with the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, if you observe the flow of the ocean currents correctly you can predict sea surface temperatures in the main hurricane development region in the North Atlantic, which can lead to accurate hurricane predictions for the next few years.’

Met Office forecasts use temperature and salinity observations from the Argo floats which go down to 2000 metres.

The project used climate models initialised with contemporaneous observations of the correct state of the ocean forced by observed sea surface temperatures, sea ice and the atmosphere.

Observed variability was aligned with simulated natural variability. External forcings such as from greenhouse gases, solar activity and stratospheric aerosols were taken from observations for past date ranges. ‘Middle of the road’ projections of their future concentrations were used.

This offered far more accuracy than climate models only forced by external factors including aerosols and greenhouse gases. Accuracy is determined through what’s called ‘hindcasting’.

Today, the Met Office is a world leader in initialised climate forecasting. The success of the practice has led to similar multiannual forecasts based on climate model predictions being developed.

The project four years on

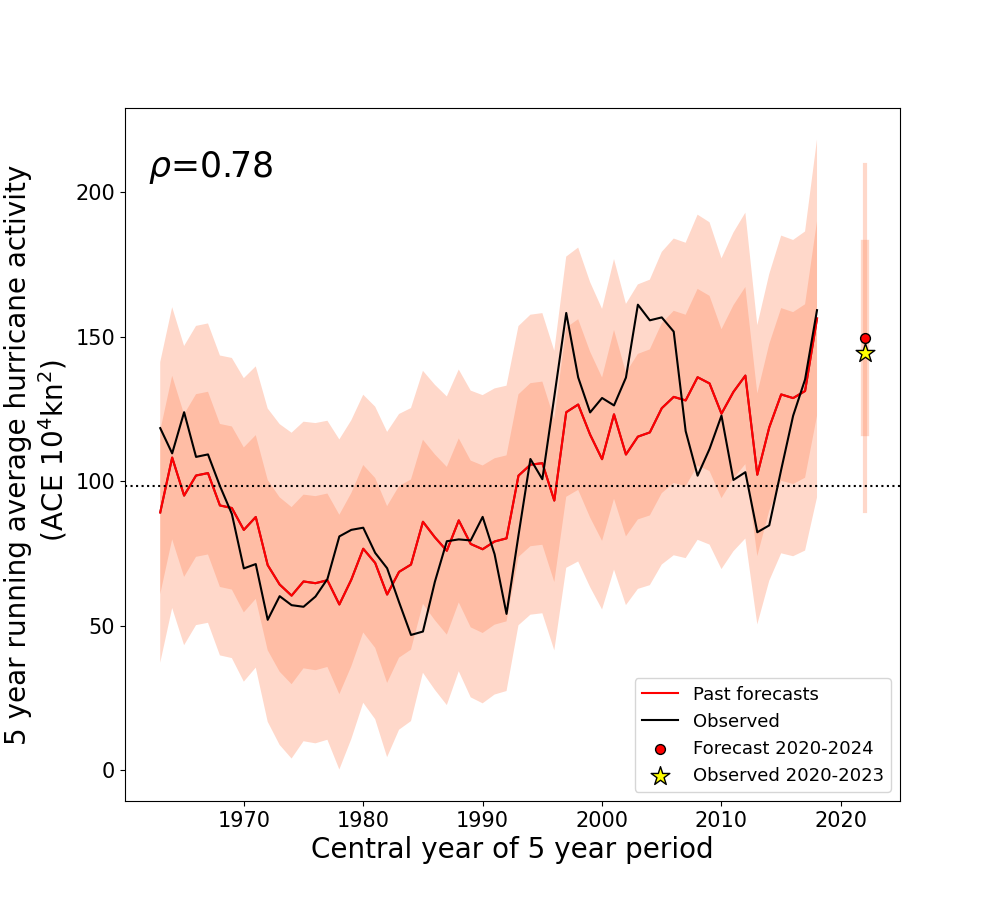

Up until the end of the 2023 North Atlantic hurricane season, real world hurricane activity was almost exactly what the Met Office predicted.

In 2019, the Met Office estimated an average accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index of 150. To date, it’s 145. The Met Office also predicted a broad range of financial loss from hurricanes on the Atlantic coast over the subsequent five-year period .

‘The middle range for 2020-2024 was $240 billion,’ Dr Lockwood says. ‘So far, the total for 2020-2023 is $260 billion. Losses have been very high and we’ve still got 2024 to come. This is obviously valuable information for WTW and their clients.’

Benefits of decadal forecasting for the insurance industry

‘Decadal and seasonal predictions provide a more relevant timescale for strategic planning in climate servicing and climate risk assessment,’ explains Dr Daniel Bannister, Weather and Climate Risks Research Lead at the WTW Research Network.

Decadal forecasts offer insights into climate variability within the next 10 years, a time frame which is more practical for current business and policy planning. Predictions also have higher spatial and temporal resolutions and provide more detailed and globally relevant climate information.

‘This granularity allows for more accurate assessments of climate-related hazard risks such as the probability of extreme weather events in specific regions,’ Bannister says.

For Bannister and the insurance industry, ‘Decadal forecasts can be thought of as indication whether the “weather dice” are loaded in favour of certain outcomes for a particular region. When trends are predicted over a decade, insurers are better able to understand and prepare for the likelihood of more or less frequent extreme weather events.’

Insurers can strategically manage their portfolios, enhancing their ability to make informed decisions without being swayed by the volatility of shorter-term predictions and events.

Ultimately, Bannister says, ‘As decadal forecasting continues to improve, we’ll see insurers increasingly use it for risk management. Accurate data and forecasts also allow our specialist consultants to communicate risk and undertake vulnerability assessments for clients around the world.’

The Met Office and the future for initialised climate forecasting

The Met Office five-year hurricane prediction project has demonstrated that, at least up until now, previously unknown accuracy is possible. When the project finishes, Dr Lockwood hopes that the five-year hurricane predictions will continue.

‘It would be great to get a few more years of predictions,’ she says, ‘because the Atlantic has been showing unusual variability in sea surface temperature recently. It has been jumping around a lot. In 2015 and 2018 it was very cold but last year there was a major heatwave. Because climate change is accelerating at the moment, it’s vital to be able to monitor and model its impact on the ocean. As with the atmosphere, a hotter ocean is driving more extremes.’

Looking ahead, Dr Lockwood hopes that ocean observing will continue to fill in the gaps about what is known about the world’s oceans.

‘The initial ocean conditions play a really large role in shaping what the climate is going to be like for the next five to ten years,’ she says. ‘So, when you make these longer-term predictions, you’ve really got to start with the right initial conditions in the ocean so that’s where ocean observing is really useful. Especially the deep observations that exist now. When ocean dynamics are better understood, we will improve our predictions.’

If this happens, and it is looking highly likely that with ocean data it will, decadal prediction science will start to become genuinely useful for decision-makers in business and government to help with strategic planning when it comes to weather and climate-related risks.